Wheat Farming in South Asia: Early Sowing Beats Terminal Heat

Farmers in South Asia, a wheat breadbasket challenged by land degradation, water scarcities, and rising temperatures and labor costs, are reaping benefits from the work of WHEAT partners to develop and spread resource-conserving cropping practices and better policies.

It is not unusual for siblings to differ, and such was the case for two brothers in Naropatti Village, Muzaffarpur District, Bihar State, India, when they decided how to manage their wheat crops. Adhering to advice from experts of the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA), Pankaj Kumar Singh sowed his crop in early November 2013 using zero tillage (seed is placed directly into unplowed soils and surface residues from the preceding rice crop) and he followed up with timely applications of irrigation, fertilizer and herbicides. “I believed this would fetch me a much higher yield than I would get from traditional practices,” Pankaj said.

His brother, Srikant Kumar Singh, did not share Pankaj’s enthusiasm for new technologies. Instead, he followed the old practices of casting the seed over the field, with few inputs and in late November. In the end, Srikant’s reluctance to innovate left him with a poor crop right next to his brother Pankaj’s vigorous wheat field. But Naropatti farmers have generally had a successful 2013- 14 wheat season, with many adopting early sowing, according to R.K. Malik, who leads work under CSISA Objective 1 to spread technologies that increase cereal productivity, resource use efficiency and incomes.

“Earlier sowing of wheat is an important adaptation to climate change in the eastern Indo-Gangetic Plains and it doesn’t cost anything, so smallholder farmers can easily benefit from the practice,”

-R.K. Malik

Leader of CSISA Objetive 1

“Earlier sowing of wheat is an important adaptation to climate change in the eastern Indo-Gangetic Plains and it doesn’t cost anything, so smallholder farmers can easily benefit from the practice,” Malik said. According to Malik, sowing wheat in late November or early December – the normal practice in eastern India – makes the crop vulnerable to late-season heat that can exceed 35 degrees Celsius and reduce wheat yields by 50 percent. “We’ve confirmed this through several seasons of on-farm experiments in Bihar and Eastern Uttar Pradesh,” Malik explained.

Moving Wheat’s Calendar Forward

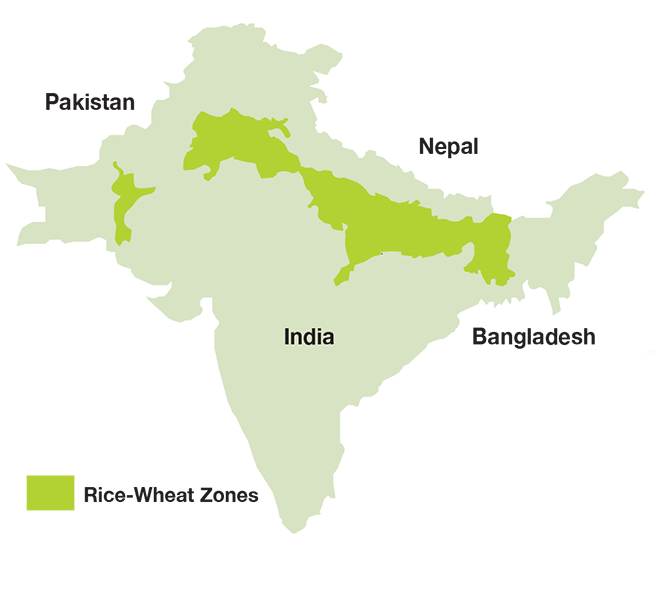

Established in 2009 and supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and USAID, CSISA promotes durable improvements in the cereal-based cropping systems of South Asia and particularly in the Indo-Gangetic Plains, an area of 700,000 square kilometers and 1.3 billion inhabitants that is South Asia’s breadbasket. CSISA involves more than 300 public, civil society and private sector partners, according to Andrew McDonald, CSISA project leader. “Together we develop and spread resource-conserving crop management technology and new cereal varieties, strategies and systems for livestock and aquaculture, and improved policies and markets in Bangladesh, India and Nepal,” he said.

CSISA partners have worked in recent years with Bihar’s Department of Agriculture, its Agriculture Management Education & Training Institute and diverse extension agencies to promote zero tillage and early sowing of wheat. During the Department of Agriculture’s planning meeting in November 2013, CSISA specialists urged extension agents and farmers to adopt early sowing of wheat to offset rice crop losses from a severe drought that year. Word spread to adjacent villages and many farmers advanced their wheat planting dates. With encouragement from CSISA, farmers also applied fertilizer and herbicide at the right times. In Kishanwada Village, early sowing of the 2012-13 wheat crop resulted in an unprecedented grain harvest of 7.3 t/ha, nearly 2.5 times the average yield in India. Based on such evidence and CSISA advocacy, the Bihar Department of Agriculture changed its official recommendations in 2014, encouraging farmers to sow wheat before 15 November.

“An ongoing survey shows that zero tillage is now used to sow wheat in 38 percent of the villages… starting from nearly zero adoption in 2009.”

-R.K. Malik

Leader of CSISA Objetive 1

Long-Term Spread of Innovation

CSISA builds on and extends the success of the Rice- Wheat Consortium (RWC) for the Indo-Gangetic Plains, which tested and promoted resource-conserving cropping practices in South Asia during 1997-2004, as documented in a 2011 case study by the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), one of the funders of that work.

“WHEAT invests one-third of its research budget on cropping systems, with a focus on sustainable intensification,” explained Victor Kommerell, WHEAT manager. “Conservation and precision agriculture-based practices save water, nutrients and energy and raise incomes, and can be adapted to serve the needs of both large- and small-scale farmers.”

For more information, contact R.K. Malik, CSISA Objective 1 Leader, Bihar and eastern UP Hub Manager.